The Forgotten Frontline: Low Wages, No Security for Pakistan’s Camerapersons

By: Sheraz Ahmad Sherazi

On a scorching summer afternoon in 2016, a bomb ripped through a crowded street in Peshawar. Among the chaos was 28-year-old cameraperson Imran Shah, racing to the scene with his camera slung over his shoulder.

He worked for a local television channel and, like many of his colleagues, was among the first to arrive. As he positioned himself to capture the unfolding tragedy, a second blast detonated a tactic often used by militants to target first responders and media crews.

Imran was hurled several feet into the air. Shrapnel tore through his leg and shoulder, leaving him with permanent nerve damage. His camera was destroyed, but the footage survived later looping for hours on television screens across Pakistan.

For weeks, he lay in a hospital bed with minimal financial support. His channel covered part of the cost; the rest came from borrowed money and donations. Once discharged, he was asked to return to work almost immediately still limping, with no counseling or rehabilitation.

“I captured the blast for the world to see, but no one stood by me afterward,” Imran recalled. “Sometimes, I wonder if my life is worth less than the camera I was holding.”

According to Reporters Without Borders, more than 130 journalists and media workers have been killed in Pakistan since 2002 — over 20% of them were camerapersons or technical staff covering bomb blasts or violent protests.

Still Behind the Lens — and Still at Risk

Nearly a decade after the blast, Imran still works as a freelance cameraperson, mostly covering social issues and press conferences in Peshawar. The physical pain remains; he walks with a slight limp. But the psychological toll is heavier.

“Every loud sound takes me back to that day,” he said. “There’s fear, but we have no choice. If I don’t work, I don’t eat.”

Where Danger, Debt, and Depression Collide

For Pakistan’s camerapersons, physical danger is only one part of a larger struggle. Behind every high-risk assignment lies a web of financial instability and emotional exhaustion.

Low pay, delayed salaries, and a lack of health or life insurance mean that most live month-to-month — while also dealing with trauma from exposure to violence.

Umar Khattab, a cameraperson from News One Peshawar, said financial uncertainty directly affects mental health.

“When we’re not paid for months, it affects our minds. We can’t focus on our work, and the stress ruins our family life.”

Saleem Khan from Express News Abbottabad echoed this:

“Reporters get salaries, but technical staff like us have to fight for our dues. If organizations delay payments, how do we survive?”

Invisible Workers: The Hierarchy Inside Newsrooms

Within most media organizations, camerapersons are classified as “technical staff,” not editorial employees. This categorization means they’re often excluded from benefits such as annual increments, medical insurance, and press club memberships.

“We are treated as if we’re replaceable equipment, not journalists,” said Akbar Balti, a senior cameraperson at 365 News. “A new recruit and a veteran often earn the same. There’s no respect for experience.”

The Lack of Training and Safety Measures

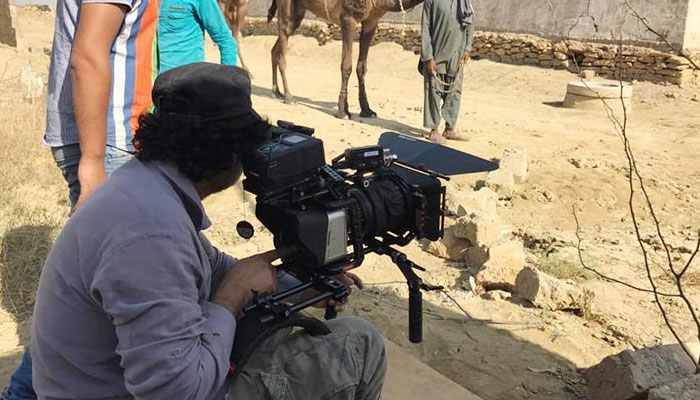

Pakistan’s media industry still lacks formal safety training for field staff. Camerapersons often learn on the job, with no instruction on how to protect themselves in conflict or riot situations.

Yasir Hussain, former General Secretary of the Peshawar Press Club, said:

“Cameramen are sent to bomb sites and protests without protective gear or crisis management training. Their lives are at constant risk.”

Workshops are occasionally organized, but attendance is low.

“Most can’t afford to skip assignments — they get paid per story,” Yasir explained.

Afzal Butt, President of the Pakistan Federal Union of Journalists (PFUJ), called for structural change.

“Our camerapersons are frontline soldiers of journalism, yet they get no protection or insurance. Media owners must take responsibility and treat them as equal partners in reporting.”

Low Wages, No Increments, and Job Insecurity

Camerapersons across Pakistan report stagnant salaries and no clear promotion paths.

Raja Ebad from Neo News Swat said:

“Most of us work on contracts that can be terminated anytime. There’s no medical coverage or pension. If we lose our job, we have nothing to fall back on.”

Shahbaz from 51 News and Ali Jan from Khyber TV added that overtime work is rarely compensated.

“Anchors and reporters earn the recognition and bonuses. We risk our lives behind the camera, yet remain invisible.”

Voices from Female Camerapersons

While the field is largely male-dominated, a small number of female camerapersons are breaking barriers — facing both the same dangers and gender-specific harassment.

There are fewer than 25 active female camerapersons in Pakistan, mostly based in Islamabad, Karachi, and Lahore.

Aneela, from HUM News, said:

“The industry thrives on our work, yet we’re undervalued. On assignments, people stare, question, or even refuse to cooperate just because I’m a woman with a camera.”

Sadia Haidri from APP added:

“We face double the struggle — low pay and constant scrutiny. I’ve covered floods, protests, and funerals, but people still think a woman can’t handle a camera.”

Female camerapersons also report safety concerns during fieldwork, particularly in conservative areas where their presence in public spaces attracts hostility.

Kashif Abbasi, President of the Television Cameramen Journalists Association (TVCJA), said the government and media industry must recognize camerapeople as equal stakeholders in journalism.

“Our members work in the most dangerous conditions protests, bomb sites, floods yet they have no insurance, no pension, no health coverage. TVCJA has repeatedly urged both the government and channel owners to implement a standardized pay scale and safety policy, but our voices go unheard.”

He added that the association plans to submit a charter of demands to the Information Ministry, seeking inclusion of camerapersons in federal media protection laws.

Legal Framework and Government Response

Pakistan’s labor laws technically cover all media employees, but implementation remains weak.

Advocate Tania Bazai noted:

“Media houses routinely violate labor rights, and workers lack the resources to take legal action.”

Advocate Bina Shahid emphasized that a clear legal category for technical media staff must be established.

“Cameramen and women are essential media workers. They deserve timely salaries, insurance, and job security under federal labor laws.”

Expert Opinions: Beyond Money — Safety and Sanity

Experts say financial reforms must go hand in hand with psychological and physical protection.

Dr. Faiz Ullah, a psychiatrist at Ayub Medical Complex, said:

“Camerapersons experience repeated trauma exposure bomb sites, funerals, disasters. Without counseling, this leads to chronic PTSD and burnout.”

He recommended mandatory trauma workshops, mental health hotlines, and peer support programs under press clubs and unions.

What Can Be Done?

Nayyar Ali, Secretary of the National Press Club, urged the government and media owners to take responsibility:

“Journalism isn’t just about anchors or editors. Cameramen are the eyes of the nation without them, there is no news.”

She called for:

-

Minimum wage standards for technical media staff

-

Insurance and risk allowances for field assignments

-

Mental health and trauma support programs

-

Legal inclusion of cameramen and camerawomen in journalist protection laws

Until then, organizations like PFUJ and press clubs must continue advocating for those on the forgotten frontline the men and women who show Pakistan the truth, often at the cost of their own safety.

“Without us,” Imran Shah said quietly, “the world would never see what really happens here. But who sees us?”.

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.