“Reporting Here is Like Walking on Fire”: Rural Journalists Struggle to Stay Safe While Delivering the Truth

By Sheraz Ahmad Sherazi

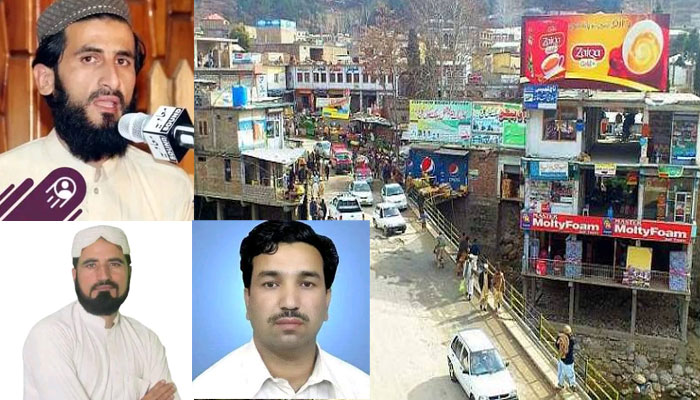

“Reporting in rural areas is like walking on fire.” These are the words of Ihsan Naseem, a senior journalist with Mashriq TV in Battagram, whose 15-year career has been shaped by fear, threats, arrests, and an unwavering commitment to telling the truth. Across Pakistan’s remote districts, journalists like Naseem risk their lives daily to report from villages where their work is often misunderstood, unwanted, and dangerous.

It would be more accurate to say that journalists in Pakistan’s larger cities generally enjoy relatively better access to legal support, press clubs, visibility, and institutional backing though they too face serious challenges. In contrast, many rural reporters work without contracts, regular pay, or legal cover, making them far more vulnerable to harassment, arrest, and violence.

“Villagers don’t understand our role,” Naseem said. “They take our reports personally and see us as enemies. We report despite life-threatening conditions and still send news to media houses, often without any payment.”

In 2023, Naseem was arrested after covering a jalsa (public rally) of Manzoor Pashteen, head of the Pashtoon Tahaffuz Movement (PTM), in Battagram. He was detained under the Maintenance of Public Order (MPO) law specifically Section 3 of the MPO which allows local administrations to detain individuals for up to 30 days to prevent what authorities deem a threat to public order.

Naseem spent 20 days in jail and faced three First Information Reports (FIRs) on charges of “spreading unrest.”

“All I did was report the rally the same way any journalist would,” he recalled. “Yet the police treated me like a criminal. I was only released after local elders intervened.” He said the experience left him deeply disillusioned with journalist bodies meant to protect reporters. “Journalist unions mostly focus on city reporters. No one sees the fire we walk through in districts like Battagram.”

The dangers are not limited to arrests. Social pressure in tightly knit rural communities can be just as suffocating.

Sher Khan, a reporter for the Daily Shumal in Battagram, described how covering sensitive issues can turn families and tribes against journalists. “We can’t report freely on issues like honor killings,” he said. “When we do, even our own relatives turn against us.”

He cited a recent incident in Ajmera village of Battagram district, where a child was allegedly kidnapped by a powerful local figure. “Because of tribal pressure and fear of retaliation, we could not report it,” he said, adding that no mainstream media coverage appeared due to the same pressures.

Sher Khan said the risks escalated further during political unrest. In the recent past, when? while covering clashes between police and demonstrators during protests by the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) in Battagram, he was allegedly beaten and briefly detained by police.

“I was just taking footage when the police grabbed me, accused me of supporting protesters, and beat me,” he said. “Later, I found out there was even an FIR against me for attempted murder completely fabricated.”

He said he approached local press club leaders for help, but received none. “One station house officer (SHO) even told me he would plant drugs on me if I didn’t stop reporting,” he alleged. “That’s the kind of fear we live with.”

Naseem Swati, a reporter with Such News based in the Hazara region, said that even routine assignments become dangerous in rural settings. “Working here means living in constant fear from society, political actors, and the administration,” he said. “We have to protect ourselves every second, and there is no system to support us when something goes wrong.”

Legal experts say this vulnerability is rooted in lack of awareness and access to justice. Advocate Nizam Ullah, a senior lawyer based in Battagram, said rural journalists are especially exposed to the misuse of laws. “Most rural reporters don’t fully know their legal rights,” he said. “They face politically motivated FIRs and the misuse of laws such as the 3-MPO, anti-terrorism provisions, or defamation charges.”

He stressed the need for institutional support. “There should be legal aid cells under bodies like the Pakistan Federal Union of Journalists (PFUJ) or in coordination with bar councils to provide emergency response, legal guidance, and pro bono services to journalists who are wrongly targeted.”

Although federal and provincial laws apply uniformly across Pakistan, the gap in implementation is far wider in rural districts. In places like Battagram, local journalists say cases against reporters often go undocumented publicly, and no consolidated data exists on how many FIRs were registered against journalists in 2024–25—highlighting the lack of transparency and oversight.

This neglect is also reflected in numbers. While urban centers in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa have hundreds of registered journalists affiliated with active press clubs, districts like Battagram have only a few dozen working reporters, many of whom are stringers without formal accreditation or employment contracts. Local journalist bodies say there is no comprehensive, publicly available breakdown comparing rural and urban journalist registration, further marginalizing rural reporters in policy discussions.

Rana Muhammad Azeem, President of the Pakistan Federal Union of Journalists (PFUJ), acknowledged the scale of the problem. “Rural journalists are the most neglected segment of our media fraternity,” he said. “They work without proper salaries, legal protection, or recognition, yet they face the highest risks.”

He said the PFUJ is drafting policy-level reforms aimed at ensuring rural reporters receive legal coverage, insurance, safety gear, and immediate legal assistance in cases of FIRs or arrests. “We have proposed that all media houses treat their rural stringers with the same dignity and benefits as city-based staff reporters,” Azeem added.

However, local unions such as the Provincial Press Union of Journalists (PPUJ) have been criticized by reporters in districts like Battagram for failing to provide tangible support. This reporter sought the PPUJ’s version on these allegations, but no response was received by the time of publication.

Kashif Uddin Syed, a senior office-bearer of the Khyber Union of Journalists, said media houses must confront their double standards. “These reporters are the backbone of our newsrooms,” he said, “yet they are ignored when they are in danger. Media houses must provide contracts, safety equipment, and legal protection.”

The toll of working under constant threat is not just physical or legal it is deeply psychological. Dr. Faiz Ullah, a psychiatrist at Ayub Medical Complex, said rural journalists often suffer from chronic anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and emotional exhaustion.

“Without counseling or peer support, they internalize repeated trauma,” he said. “Over time, this leads to serious long-term psychological issues.” He called for mental-health helplines and trauma-management workshops specifically tailored for journalists working in high-risk and remote areas.

Despite arrests, threats, and social isolation, rural journalists continue to act as a fragile lifeline between Pakistan’s most isolated communities and the rest of the country. They work unpaid, unarmed, and unsupported yet they carry the burden of stories that would otherwise remain buried in silence.

Their courage deserves recognition. Their safety demands action.

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.