Gilgit-Baltistan’s Vanishing Green Veins

Deforestation, unplanned urban growth, and climate change are choking Gilgit-Baltistan’s natural lifelines — and turning its postcard beauty into a looming ecological disaster.

GB’s Vanishing Green Veins

By Dr. Attarad Ali,

Nestled within the shadows of the world’s mightiest mountain ranges, the Karakoram, Himalaya, and Hindu Kush, Gilgit-Baltistan (GB) is often lauded for its stunning landscapes, glacial rivers, and pristine wilderness. Yet behind this postcard-perfect image lies a grim reality of environmental degradation, systemic neglect, and an unfolding ecological crisis. What was once a haven of biodiversity and climatic stability is now reeling under the weight of rapid deforestation, urban sprawl, unchecked non-local migration, and a climate emergency spiralling beyond control. Gilgit City, the region’s administrative and economic nerve center, is bearing the brunt of these transitions and the consequences are both visible and devastating.

Alarming Decline in Forest Cover

Over the past two decades, GB has witnessed an alarming transformation in land use, driven by population pressure, commercial interests, and short-sighted governance. Forest cover, which once cloaked over 640,000 hectares of its territory, has plummeted to an estimated 295,000 hectares, barely 3.6% of the total land area. A region once proud of its chinar-lined valleys, aromatic Gunair trees, and dense groves of mulberry and poplar has been systematically stripped of its natural armour. This loss has not been incidental, it is the direct result of relentless cutting of trees for fuel, timber, and furniture, often facilitated by informal logging mafias and shielded by regulatory inertia.

Economic Drivers of Deforestation

The motivation behind this destruction is as economic as it is aesthetic. Expensive hardwoods like deodar, cedar, and pine are routinely harvested and fashioned into ornate wall panelling, flooring, and furniture for homes and offices of the privileged elite. These woods, once vital parts of high-altitude ecosystems are now status symbols in the drawing rooms of bigwigs. Even government buildings in GB exhibit this irony, adorned with wood panels sourced from trees that should have stood to stabilize slopes, purify air, or intercept floodwater. The cultural and ecological value of trees, once known for their aromatic oils and soil-binding roots, has been reduced to decorative veneer.

Foreign Elements and Militants Exposed in Bajaur

Environmental Consequences of Tree Loss

This unregulated removal of vegetation has come at an enormous cost. Deforestation in GB directly contributes to soil erosion, altered precipitation patterns, and the escalation of floods and landslides. Scientific data from Shigar and Hunza valleys reveals that average soil erosion rates increased from 7.5 to nearly 9.1 tons per hectare per year between 2005 and 2015, a trajectory largely attributed to forest loss and the paving over of formerly absorbent soils. In tandem, annual forest loss in GB and adjacent Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) is estimated at 27,000 hectares, dramatically reducing the region’s carbon sink capacity and exacerbating local warming. These microclimatic changes, in turn, accelerate glacial melt, destabilize mountain slopes, and reduce the natural resilience of watersheds.

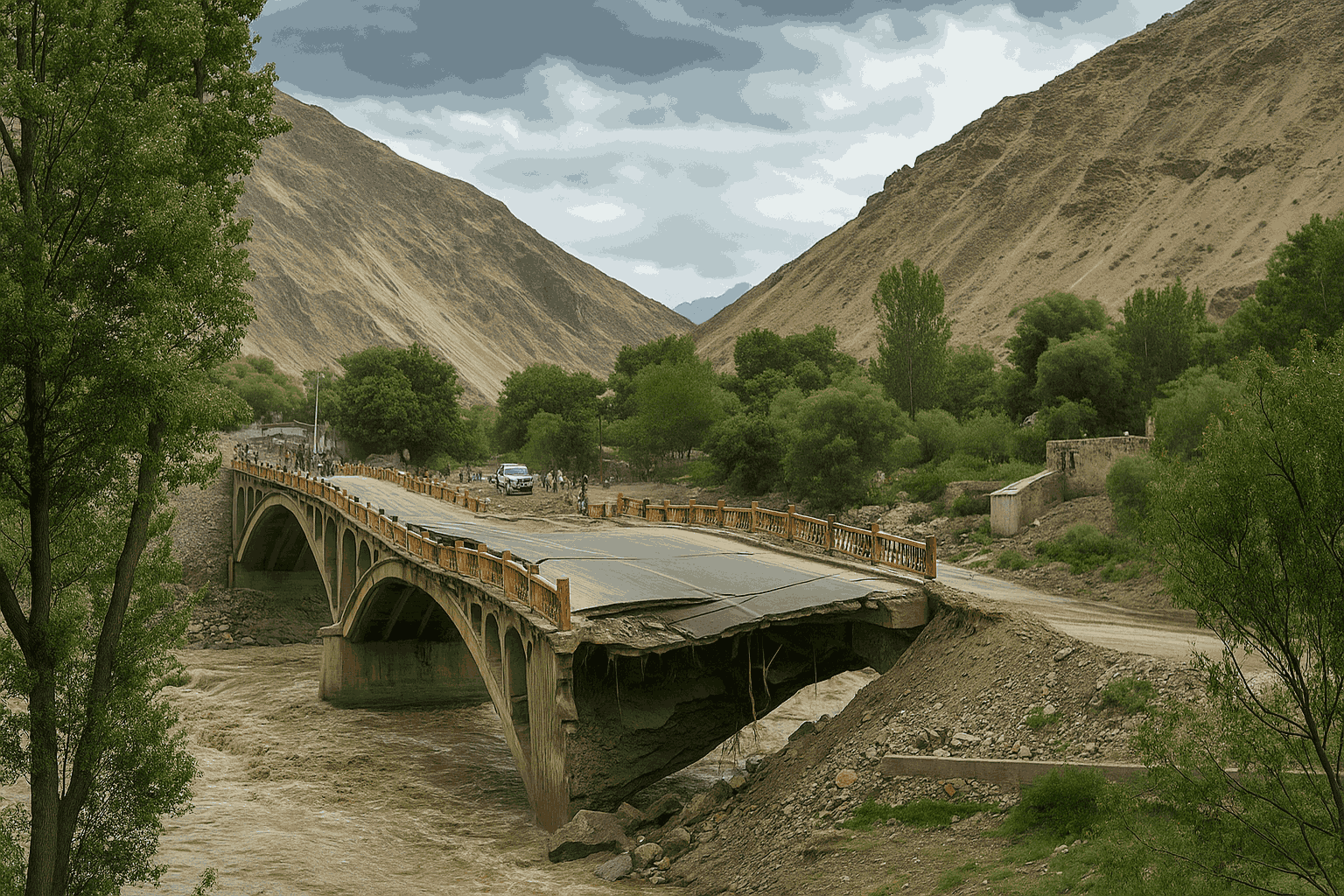

Summer 2025: Record Heat and Devastating Floods

The results have been catastrophic. In the current summer of 2025, GB experienced one of its worst natural disasters in recent memory. Temperatures soared to an unprecedented 48.5°C, triggering rapid glacier retreat and glacial lake outburst floods (GLOFs) across the region. Over 72 people lost their lives, hundreds were displaced, and critical infrastructure bridges, homes, power plants, and farmland was washed away in a matter of days. Gilgit City, built along a floodplain with aging drainage systems and encroached waterways, was severely affected. Streams like Jutial Nala, once surrounded by herbs, trees, and natural filters, have become narrow, cemented drains choked with plastic and sewage. These formerly healing watercourses now act as accelerators of flood damage rather than barriers.

Urbanization and Population Pressure on Gilgit City

The situation is compounded by an unprecedented wave of migration and urbanization. Gilgit City’s infrastructure was initially designed to support around 200,000 residents. Today, it grapples with an estimated population approaching more than half a million, much of it driven by non-local settlers attracted to opportunities in tourism, trades, and administration. This surge has led to the unplanned expansion of markets, housing colonies, and concrete structures often at the cost of prime agricultural land, riparian buffers, and the few remaining green belts. Where once stood chinar groves and mulberry orchards are now blocky shopping plazas, congested streets, and heat-trapping rooftops. Traditional architectural knowledge, which once integrated local materials and airflow design, has been replaced by imported styles that ignore the region’s unique climatic needs.`

Public Health Risks from Water and Waste Pollution

With this transformation has come a cascade of public health hazards. According to water quality assessments conducted in Gilgit City, 100% of tap water samples tested were found to be microbiologically contaminated with E. coli and other coliform bacteria, rendering it unsafe for drinking without filtration or boiling. Excessive contamination of water by heavy metals and inorganic waste poses serious health risks, including cancer, severe infections, and kidney failure and is often resistant to removal by conventional, advanced, and even state-of-the-art treatment methods such as chlorination, tertiary treatment, biological, chemical, reverse-osmosis, and nanotechnology-based techniques. Gilgit River, which provides water for both drinking and irrigation, is burdened by untreated sewage, chemical runoff from small factories, automobile workshops and the burning of municipal waste along its banks. The persistent incineration of plastic, rubber and leather waste in open air not only releases dioxins and furans, highly toxic compounds, but also contributes to a growing burden of respiratory illness, especially among children and the elderly. Add to this a waste crisis: Gilgit alone generates around 11 tons of only plastic per month, with less than 5% recycled.

Pakistan govt ‘cancels’ sugar import tender

Biodiversity Under Threat

These mounting ecological and public health crises are intimately tied to the degradation of biodiversity. GB is home to more than 54 mammal species, including the elusive snow leopard, Astore Markhor, Himalayan ibex, and brown bear. The habitat of the snow-leopard already squeezed by warming temperatures and prey decline has become increasingly fragmented due to roads construction, poaching, and tree loss. The estimated 300–400 snow leopards in Pakistan (80% of which are thought to roam GB) are under threat of losing up to 30% of their habitat in the coming decades. Meanwhile, community-managed conservation areas (CMAs), once touted as success stories in places like Kargah and Bagrot, are under-resourced and lack legal protection against encroachment or overgrazing.

Policy Failures and Mismanaged Projects

The story of environmental decay in GB is not one of natural inevitability, it is one of human negligence, policy failure, and economic exploitation. Despite repeated warnings from ecologists, local civil society, and development organizations, meaningful interventions remain scattered and insufficient. UNDP-funded GLOF projects, despite receiving billions, were poorly managed and widely misused, diverted toward luxury vehicles, personal leisure trips, and ineligible appointments, rather than addressing the needs of affected communities. As a result, the region remained vulnerable to catastrophic floods and infrastructure damage, leading to the project’s overall failure. Programs like afforestation campaigns led by the Aga Khan Rural Support Programme (AKRSP) or the GB Environmental Protection Agency’s “green loans” for eco-businesses are commendable, but limited in scale. What is urgently needed is a multi-tiered response: enforceable zoning regulations, a regional forest protection authority with autonomous powers, mandatory green belts and urban forestry in city planning, and massive investment in clean energy to reduce fuelwood dependence.

Ireland’s Prendergast shines as Pakistan falter in T20I series opener

Pathways to Environmental Recovery

The potential for recovery exists. Native species such as willow, poplar, apricot, sea buckthorn, and the aromatic Gunair can be reintroduced along stream banks, rooftops, and roadsides to restore microclimates and revive soil fertility. Stream desilting and biological wastewater treatment must be prioritized to rehabilitate natural filtration systems. Public campaigns can build awareness around the cultural value of trees, urging citizens to plant, protect, and preserve. Educational institutions like Karakoram International University (KIU) Gilgit and the University of Baltistan Skardu (UoBS) can lead research on climate-resilient agriculture and community forestry. Most crucially, migration and construction must be regulated to prevent the continued conversion of natural landscapes into impermeable concrete deserts.

A Critical Crossroads for Gilgit-Baltistan’s Future

Gilgit-Baltistan faces severe deforestation, glacier melt, climate crisis, and urbanization, threatening ecosystems, water, and livelihoods.The fate of GB and by extension, much of northern Pakistan hinges not only on glacier health or seasonal rainfall but on the forests, soils, and waters that act as invisible safeguards. In the race toward modernization, we have forgotten that true progress does not come at the cost of ecological collapse. Gilgit City stands today as a warning and an opportunity: it is time we listen to its silence, before floods, fires, and falling trees do the talking for us.

Dr. Attarad Ali

Environmentalist

Director Quality, at University of Baltistan, Skardu

Gilgit-Baltistan

Email: attarad.ali@uobs.edu.pk

Contact: +923133353565

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.