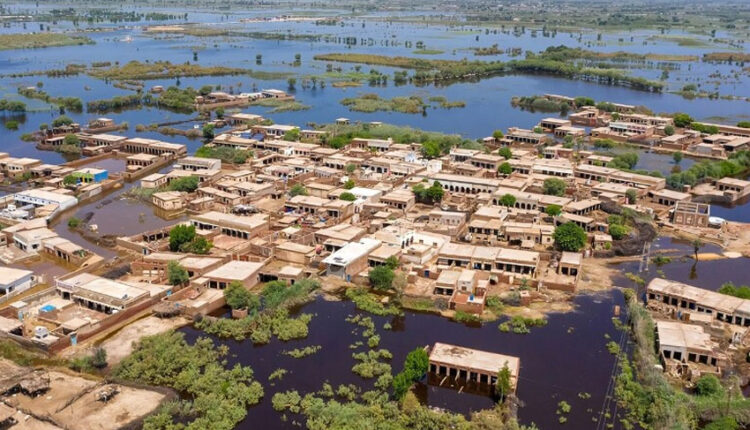

As Pakistan was hit by heavy rains once more in August 2025, over 7,001 homes were demolished, 1,204 people were hurt, and over 785 people died. Images of entire communities reduced to rubble, villages engulfed by rivers, and families stranded on rooftops were eerily familiar. However, the failure of our state and society to learn from past tragedies may be the most tragic aspect of this story, rather than the flood itself.

Its own lack of readiness has previously overtaken Pakistan. More than 1,700 people were murdered, and nearly 20 million people were affected by record-breaking floods in 2010. It was regarded as one of the worst humanitarian catastrophes in contemporary history at the time. Thirty-three million people were displaced, nearly two million homes were destroyed, and 1,739 people were killed when floods occurred again twelve years later in 2022. The economic loss exceeded $30 billion, and entire districts were inundated. The story is repeated virtually word for word in 2025. The main distinction is that, although the numbers are lower, they still show a massive failure.

Why isn’t Pakistan ready yet? Given that history has already written about natural disasters, why do we still perceive them as surprises? Pakistan is one of the ten most climate-vulnerable nations in the world, according to several warnings from both domestic and foreign climate specialists. We are aware that our rivers will continue to be threatened by stronger monsoons and glacial melt. However, each flood season comes as an unexpected visitor, leaving people stranded and governments unprepared.

The problem lies with the government system, not the weather. The current safety measures are scattered, reactive, and poorly funded. Pakistan lacks a comprehensive flood management plan. The drainage systems are old, the dams are not well-maintained, and the embankments are weak. Local governments often respond with temporary solutions instead of building long-lasting resilience. Each year, emergency camps, food rations, and charity appeals cost billions, but the infrastructure needed to prevent these disasters is rarely funded.

Even more concerning is the lack of political will. Promises of improvements have been made by successive governments, but they have vanished as fast as the villages. The 2010 floods prompted promises of disaster preparedness units, river training, and early-warning systems. Following the 2022 disaster, worldwide commitments were made to “build back better.” However, in 2025, as families grieve their lost loved ones and rebuild their homes by hand, we have to wonder: where did those promises disappear to? As soon as the waves subsided, were they forgotten and reduced to platitudes for TV screens?

Even more damaging than the humanitarian damage is the political silence. Floods are not only a natural tragedy; they also serve as a gauge of how well the government protects its most vulnerable residents. And by that metric, Pakistan has consistently fallen short. What does progress actually mean if rural farmers lose their crops every three years, if women have to carry their kids through chest-deep water every monsoon, and if teenagers have to watch their education be drowned by swamped schools?

We cannot continue to hold nature responsible for our carelessness. Flood-resilient systems have been developed in nations with significantly higher climatic threats. For example, Bangladesh has made large investments in flood shelters and community-based warning systems, which have greatly decreased the number of victims. Why has Pakistan failed to duplicate such models despite decades of experience and billions of dollars in aid?

More than fleeting pity is required in response to the frequent floods; accountability is required. The moment has come for our federal and provincial governments to provide honest answers. What prevented drainage channels from being cleared before the monsoon? Why is the expansion of housing developments into floodplains permitted? Why is our national climate adaptation policy still ineffective? The most crucial question is: why must the poorest citizens bear the brunt of our failure, already weighed down by unemployment and inflation? ABOVE ALL THREE PARAS ARE ENDING WITH A QUESTION MARK???

Disaster prevention must replace disaster relief if Pakistan is to endure the century of climate change. This entails the construction of dams and reservoirs, the enforcement of urban planning regulations, the provision of tangible resources to the National Disaster Management Authority, and the reinforcement of local governments to enable prompt responses. It also means that floods should be viewed as a permanent aspect of our landscape that requires long-term solutions rather than as an isolated disaster.

As always, the seas of 2025 will subside. Promises will be made, politicians will visit the camps, and photo ops will be conducted. However, the scars left by the flooding will not go away for the farmer who lost his wheat field, the girl who lost her school, or the family who lost their house. Pakistan will continue to drown in its own mistakes as well as in the sea unless we end this cycle of carelessness.

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.