A Constitutional Question We Can No Longer Avoid Why Pakistan must clarify its role in Qur’an education

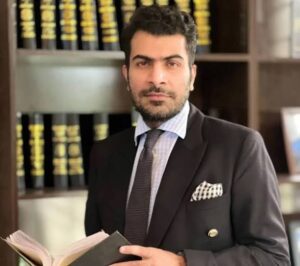

By: Malik Aneeq Ali Khatana

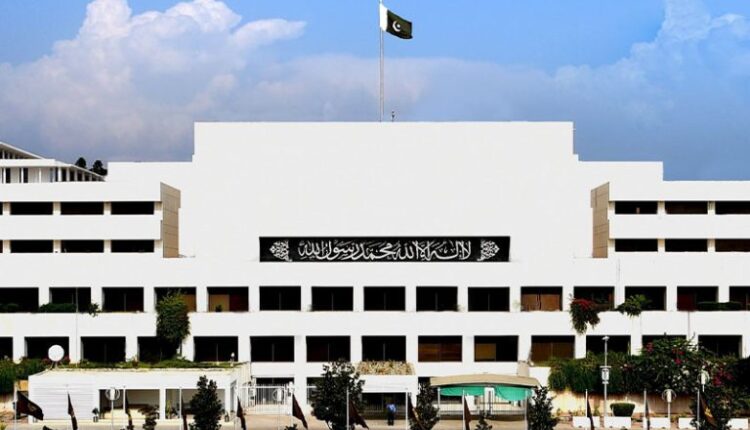

Pakistan was founded on the name of Islam, and our Constitution makes that clear from its very first lines. The Objectives Resolution, now part of the Preamble, declares that sovereignty belongs to Allah alone and authority is delegated to the State as a sacred trust. Yet even after 78 years of independence, we face a simple but vital constitutional question: What is the State’s clear, enforceable duty to ensure every Muslim child can not only recite the Holy Qur’an but also understand its true meaning and live by its guidance? I have filed this petition directly in the Supreme Court under Article 184(3). It is not to favor any sect, promote one scholar over another, or limit genuine religious scholarship. It is a lawyer’s demand for plain answers from the Constitution so the law can be followed exactly as written, without excuse or delay.

Article 31 states the State’s duty without any doubt or ambiguity. Clause (1) commands: “The State shall endeavour to enable the Muslims of Pakistan, individually and collectively, to order their lives in accordance with the fundamental principles and basic concepts of Islam.” Clause

(2) is even more direct: “The State shall endeavour to make the teaching of the Holy Qur’an and Islamiat compulsory…” Clause (3) adds the duty to facilitate learning Arabic, and Clause (4) requires “steps to enable Muslims to understand the exact meaning of the Holy Qur’an.” These words are set in law, binding on every government that takes oath under this Constitution. But in practice, things are far from clear or uniform. Some rules come from provinces under their education powers. Others come from federal ministries. There are gaps everywhere, and worse— contradictions that leave our children confused.

Consider the translations taught in schools alongside recitation, which many provincial laws now make compulsory. Which translation should state institutions use? Is there even one official Urdu version that has been properly approved and signed off by leading scholars representing all recognized schools of thought in Pakistan—Sunni, Shia, Deobandi, Barelvi, Ahl-e-Hadith, and others? Has the federal or any provincial government formally notified such a version through a gazette? If yes, is it being used consistently across all public schools, colleges, and exams from Karachi to Khyber? If no—and from what I have seen in official records, the answer appears to be no—then why has this clear constitutional duty under Article 31(4) remained undone for decades? Provinces like Punjab have passed the Quran Compulsory Teaching Ordinance 2018, and others have similar laws, but they dodge the translation question or pick versions without consensus. This is not a fight over faith or personal belief. It is about good government—proper policy, administrative order, and strict duty under constitutional law.

Pakistan is a nation that constitutionally respects multiple schools of thought, as affirmed in various judgments and the Council’s of Islamic Ideology framework. When state-run schools, boards, and exams use different translations at random—sometimes one scholar’s work in Lahore, another’s in Quetta—it creates real confusion for our children who must pass the same national exams. Classical tafsir, that great and beautiful work of dedicated scholars over fourteen centuries from Imam Tabari to modern times, needs no government approval or rubber

stamp to live on. It has stood alone through empires and caliphates. But when the State itself steps in as educator—setting required courses, conducting tests, issuing certificates—it must provide one clear, notified standard for its own institutions. Not to end scholarly variety or private diversity, but to give every child from every background the same fair and solid base on which to build deeper understanding later in life.

The core of my petition is this precise legal question: When the Constitution orders the State to facilitate and provide Qur’anic education under Article 31, who exactly must carry it out and ensure uniformity? Is it the sole duty of the federal government, where Article 31 resides in the Constitution? The provinces, to whom education was largely devolved by the 18th Amendment? Or some coordinated mechanism between both, as the framers perhaps intended? This clash has gone unresolved too long, breeding inaction and legal uncertainty. My petition seeks a binding declaration to end the mess once and for all.

Let me state plainly and categorically what this case does not seek, to remove any doubt. It does not ask to ban other translations in private use. It does not seek to stop private madrasas, personal study, or family learning from any tafsir they choose. Article 20 protects every citizen’s freedom of religion, thought, and belief completely—no petition can touch that sacred right. What it does seek is simple justice: The State cannot pass laws making Qur’an classes required by statute in public institutions and then leave the essential details unclear or inconsistent. If state schools and colleges teach translation as part of compulsory education, there must be one single, officially notified standard for all of them. If such a standard already exists in some government file, bring it out and show it to the nation. If not, say so openly, form the consensus, and notify it without further delay. This is proper rule of law and constitutional obedience. It is not interference in faith, but faithful service to it.

Debate on Islamic provisions in our Constitution often becomes nothing more than political noise

—election slogans one year, forgotten the next. By invoking the Supreme Court’s original jurisdiction, I aim to shift this entirely—from empty words and partisan posturing to firm, enforceable orders that bind every future government. A true Islamic republic in the 21st century cannot function on unclear terms or selective compliance. Clarity is not optional; it is required, above all on something as fundamental as Qur’anic education for our rising generation. Whatever the Court ultimately rules, this petition has already won one vital point: It has forced the federal government and all four provincial governments to state their official stand on Article 31 implementation in sworn replies and affidavits. That kind of structured, on-record institutional dialogue was needed for years, if not decades.

Courts do not create religious law or pick between scholars—they have no power and no business doing so. Their job is to interpret and enforce what the Constitution already says in clear terms. The Holy Qur’an guides the lives and conscience of most Pakistanis, rich and poor alike. Its teaching in state institutions must therefore be set by clear rules, uniform across the land, and true to the letter and spirit of the law. That is no mere policy choice for politicians. It is a legal command from the supreme law of the land. The question now rests squarely with the Federal Constitutional Court. We Pakistanis—lawyers, teachers, parents, citizens—must meet it with care, truth, determination, and one united voice.

Malik Aneeq Ali Khatana is a practicing lawyer. Reach me at: malik.aneeq.ali@gmail.com (Word count: 852)

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.