Gilgit-Baltistan, with its breath-taking landscapes and strategic significance, continues to suffer from neglect in one of the most critical sectors of human development: higher education. Despite being a region of nearly two million people and considered Pakistan’s crown jewel due to its location, resources, and tourism potential, GB still struggles with the most basic educational infrastructure, leaving its talented youth with little choice but to migrate to the cities of Punjab, Sindh, and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa in search of professional and academic opportunities. At present, only two general universities cater to the entire population of the region; the Karakoram International University (KIU) in Gilgit and the University of Baltistan (UoBS) in Skardu. These institutions, though promising in their inception, are severely handicapped by limited funding, inadequate resources, and a chronic lack of infrastructure such as well-equipped laboratories, digital libraries, and research facilities. The faculty in both universities include many foreign-qualified scholars from prestigious international institutions, yet their potential is stifled due to the absence of basic facilities and weak institutional leadership, which is often compromised by nepotism and favouritism in appointments, instead of merit-based selection of visionary Vice Chancellors who could have guided these universities to excellence. This leadership vacuum has allowed a culture of patronage (sifarish) to take root, demoralizing faculty, staff and students alike and pushing the universities further down in performance rankings.

The lack of diversity in higher education opportunities in GB is glaring when compared with other provinces of Pakistan. Punjab and Sindh host dozens of specialized universities in fields such as medicine, engineering, law, and pharmacy, while GB remains entirely deprived of such critical institutions. The absence of a medical college or university is especially alarming in a region where healthcare infrastructure is weak and where patients must often travel hundreds of kilometres to Islamabad, Rawalpindi, or Karachi for specialized treatment. Establishing a medical college in GB would not only create opportunities for local youth aspiring to become doctors but would also strengthen the healthcare system by producing professionals trained in and committed to serving their own communities. Similarly, the establishment of an engineering university, particularly with departments in civil and electrical engineering, is urgently needed. GB is the epicentre of hydropower projects, road construction under CPEC, and ongoing infrastructure development, yet the majority of technical work is outsourced to contractors and engineers from outside the region. Training local youth in these disciplines would not only provide employment but also reduce dependence on outsiders, ensuring that the economic benefits of development projects remain within GB.

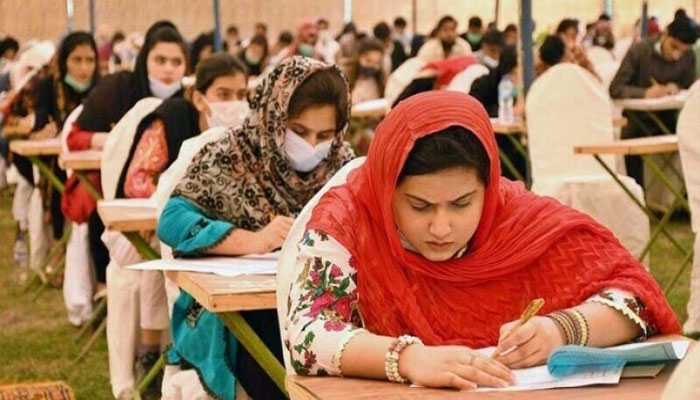

Equally dire is the absence of law schools in the region. Students aspiring to pursue an LLB are forced to migrate to Islamabad, Lahore, or Karachi, incurring high costs and exposing themselves to the difficulties of living far from their families in a conservative society where safety and proximity to home are considered among the most significant factors in university selection. In fact, a survey of GB students revealed that 92 percent consider campus safety essential, while 90 percent emphasized campus amenities, and 89 percent stressed the importance of proximity to home. This proves that for most families, sending children especially daughters to universities far away is not feasible. Establishing law departments within UoBS and KIU would therefore provide accessible legal education and would also build a cadre of lawyers trained to address GB’s unique constitutional limbo and governance issues.

The untapped potential of medicinal plants in GB highlights another missed opportunity. The region is home to rare and globally valuable medicinal flora, yet without a pharmacy or biotechnology departments, this natural treasure remains largely unexplored. Establishing pharmacy programs would allow students and researchers to study, catalogue, and commercialize medicinal plants, potentially developing a pharmaceutical industry that could not only serve Pakistan but also export herbal medicines internationally. Such an initiative would create jobs, foster entrepreneurship, and preserve indigenous knowledge, while also connecting the region to global research and industry networks.

Unfortunately, the current state of higher education in GB is characterized by an overemphasis on degrees without skills. Thousands of students graduate each year from UoBS, KIU, and affiliated colleges, yet the majority remain unemployed due to a mismatch between their degrees and the job market. Graduates with traditional degrees in life/natural sciences, arts and social sciences often find no opportunities and end up joining the ranks of the unemployed, leading to social frustration, rising poverty, and in some tragic cases, suicides. There are also increasing reports of educated youth being drawn into petty crimes such as theft, street snatching, and even extremist tendencies when opportunities remain absent. The overproduction of graduates without quality education or employable skills has turned higher education into a liability rather than an asset, both for families and for the nation. This is why industry-academia linkages are urgently needed. Instead of universities merely distributing degree papers, they must partner with industries in tourism, agriculture, energy, IT, and handicrafts to ensure that graduates acquire the technical, entrepreneurial, and innovative skills required for meaningful employment.

Tourism, for instance, is the single most important driver of GB’s economy. The region received over 1.4 million tourists in 2018, with tourism contributing a record 33.5 percent to GB’s GDP that year. In 2015, the sector contributed 8.28 percent, and by 2017 it had risen to 23.16 percent. Yet the volatility of tourism is evident: in 2020, when travel restrictions and security concerns took hold, the sector’s contribution collapsed to just 12.7 percent. Despite these fluctuations, the sector continues to employ thousands of people in hospitality, transport, guiding, and handicrafts, while indirectly benefiting agriculture, retail, and construction. However, the benefits are unevenly distributed, concentrated mainly in Hunza and Skardu, while districts like Ghanche, Ghizer, Gilgit and Astore remain marginalized. Moreover, tourism-related jobs are often seasonal and informal, lacking social security and stability. Here again, universities could play a transformative role by offering programs in hospitality, tourism management, eco-tourism, and environmental conservation, thereby professionalizing the sector and ensuring that its benefits are widely shared. Without such interventions, GB risks allowing tourism to become another wasted opportunity; a sector with immense potential but plagued by weak policies, poor infrastructure, and a lack of skilled manpower.

In parallel, vocational training is emerging as a ray of hope. The National Vocational and Technical Training Commission (NAVTTC) has introduced skill-based programs in GB that are equipping youth with employable skills in fields such as carpentry, plumbing, hospitality, and information technology. These initiatives, though still limited in scope, are highly appreciated by communities because they provide immediate employment opportunities and dignity of labour. Expanding NAVTTC’s presence and integrating its programs into the curricula of UoBS and KIU could dramatically reduce unemployment and turn GB’s youth bulge into a youth dividend.

Underlying all these challenges is the crisis of governance and funding. Both UoBS and KIU receive disproportionately low funding from the federal government, leaving them unable to hire the required faculty members, upgrade labs, libraries, and digital infrastructure. Faculty members struggle to conduct research due to the absence of grants, and students are denied modern facilities that are standard elsewhere in the country. A comparative study of schools in GB showed that while average efficiency across government schools was 92 percent, some districts such as Ghanche lagged significantly, with boys’ schools recording efficiency scores as low as 65.8 percent. Girls’ schools, however, performed relatively better, highlighting both the potential and the inequities within the education system. Moreover, while GB’s overall enrolment rate stands at 85 percent; higher than the national average of 81 percent, the Diamer district remains a black hole, with the lowest enrolment and particularly poor performance in girls’ education. This means that even before students reach university, inequalities in access to quality schooling persist, feeding into the disparities at higher education levels.

The international community has long recognized GB’s vulnerabilities. The World Bank in 2020 identified tourism as a potential solution to unemployment in rural areas, yet due to GB’s unresolved constitutional status under UN resolutions, the Bank and other global institutions are restricted from operating directly in the region. This denial of international investment and development assistance deprives the people of GB of critical projects in health, education, and environment, at a time when they face repeated natural disasters such as floods, landslides, rockfalls, and glacial lake outburst floods (GLOFs). The people of GB cannot be made to wait indefinitely for constitutional clarity while their lives and livelihoods remain at risk; urgent policy action is needed to safeguard their rights and dignity.

It is clear that the way forward lies not in establishing more general universities, which would only add to the number of unemployed graduates, but in strengthening and diversifying the existing institutions. UoBS and KIU must be provided with sufficient funding, cutting-edge facilities, and above all, visionary leadership. The appointment of Vice Chancellors must be based on merit, academic excellence, and administrative integrity, free from nepotism and favouritism. Only leaders with strong academic records and fair management practices can steer these universities out of their current decline and transform them into engines of innovation and development. Simultaneously, specialized universities in medicine and engineering must be established, while law and pharmacy departments should be launched within existing institutions. This multi-pronged approach would not only provide accessible higher education but also create professionals who can directly address the region’s health, infrastructure, legal, and economic challenges.

Education is the only sustainable industry in GB. With limited business opportunities, almost no large-scale industries, and scarce government jobs, the people of the region depend almost entirely on education; either to seek employment abroad or to secure positions within Pakistan. If education fails, everything else collapses. That is why strengthening higher education in GB is not merely a regional demand; it is a national imperative. The future of Pakistan’s northern frontier depends on how seriously the state addresses these long-standing issues. To ignore them any further would not only be an injustice to the people of GB but also a strategic mistake that undermines the country’s stability and prosperity. Neglecting higher education in Gilgit-Baltistan is not just a regional oversight; it is a national failure with profound consequences. For Pakistan, a country striving to harness the potential of its youth bulge, ignoring the aspirations of GB’s students means wasting one of its brightest reservoirs of talent. For the people of Gilgit-Baltistan, it means watching dreams turn into despair, migration into exile, and opportunity into loss. If the federal government is serious about national integration, sustainable development, and social stability, then the time to act is now.

Author:

Dr. Attarad Ali

Addl. Director of Quality, at University of Baltistan, Skardu

Gilgit-Baltistan

Email: attarad.ali@uobs.edu.pk

Contact: +923133353565

CNIC No. 71501-9627443-1

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.